We started our day last Wednesday by driving past a walkout of Hispanic students from a nearby high school. It was early in the morning, just after classes had gotten under way, and the Children’s Crusade was already marching into the headwind: By that time, the walkouts were old news, and there were no media around to chart the trickle of this out-of-the-way tributary.

The protest consisted of maybe 15 or 20 students, many of them holding or waving the now-predictable Mexican flag. They were accompanied by four school district cops, with two supremely bored-looking HPD officers standing by as back-up. For some reason, the entire desultory procession had come to a halt in the parking lot of a CVS. It was way too far to ankle it all the way downtown, so there would be no dipping into the City Hall Reflecting Pool for this bunch.

The only visible camera was wielded by a student who was videotaping his buddies. Everyone appeared to be having a good time, mugging for the camera. Several of the girls had rolled up their shirts to show off their navels, which they’re not allowed to bare in school, and a couple of the guys seemed to be throwing gang signs at passing motorists, although we’re pretty sure they weren’t real gang signs---just the cocking of the wrists and outward gliding hand motions from the chest that are as meaningless to us as the illegible graffiti that now seems to be covering every accessible public space in southwest Houston. Pre-packaged, paint-by-numbers attitude.

Nothing but blare. We could barely raise a sneer as we wheeled onward, and even felt a pang of sympathy: Yes, we too took every opportunity to miss class back when we were in high school.

Eight hours later our daughter climbed into our car in fit of high-pitched indignation as we picked her up from her school: “Do you know what (so-and-so) Bush wants to do now?” she asked. “No, what?” we replied. “He wants to send all the illegal immigrants back to Mexico!” Her friend C----, a fellow 6th grader, had been crying most of the day. C----‘s parents are illegal, and C---- feared that her family would soon be sent packing.

Naturally, this story struck a deeper chord with us than the sight of the navel-flaunting truants.

Seizing the Teachable Moment, we explained to the 12 year old that it was unlikely that C----’s parents will be forced back to their home country, as we just can’t see Americans having the stomach to sanction the round-up and deportation of 11 million or so people (much less be willing to pay for it), although it was remotely possible they might have to return to Mexico at some point and wait in line to get back in legally.

Then we tried to point out that there was a lot more than Bush driving the movement to tighten immigration laws, and that Bush, in fact, was considered a liberal on the issue by many in his own party.

“There’s probably gonna be some way that C----’s parents can stay in the country, whether it’s called amnesty or not, and hopefully C----'s family will take advantage of that, even if it costs them,” we said. “And they better do it, ’cause after whatever laws are passed it’s probably gonna be a lot more difficult to get across the border, and not so easy for businesses to hire people who aren’t here legally.” She nodded.

We went to explain that many, many people wait in line in Mexico and elsewhere for the opportunity to become U.S. citizens, and it would be fundamentally unfair to those who pursue the legal path if everyone in this country illegally were deemed automatically eligible for citizenship, with no attendant cost.

She nodded again. Fairness is a concept that 12 year olds instinctively grasp.

“So why do people come here illegally?” she asked. “Well, you know that. Think about it---who mows the lawns in our neighborhood (besides our lawn)? Who builds the houses and surfaces the roads? Works in the kitchens, sweeps out the offices … etc.” We talked of the father of her two friends who used to live down the street, a Mexican-American who ran a crew that did foundation repair, tree-trimming and whatever other hard work was available, and had his guys gather every morning in his front yard before they left for the day’s job. “Those little guys” ---none of them seemed to be over 5’4”---“were all illegal. They’re typical: They came here to work, to do the jobs that Americans won’t do, supposedly … "

But, we continued, stretching the Teachable Moment into the Teachable 15 Minutes, the reason Americans won’t do lots of those jobs is that employers can get away with paying illegal workers less, much less, and don’t have to provide them with benefits, and that dynamic drives down wages for lower-skilled workers, especially African-Americans, and … there’s more to civic life, to the culture (or “culture,” as our daily newspaper has put it) and the soul of a place or country, than cheap labor (and by the way, slavery was the ultimate in cheap labor, and look how much it did for the South---not just for African-Americans, but the 90 percent of whites [and their descendants nigh unto the generations] who never owned a slave … )

(We did not explain that what we mean by

culture has nothing to do with skin tone, religion, taste in food or music or the number of cars you park in your front yard, or any other factors aside from an understanding of [no matter how unschooled] and adherence to the Constitution---what sets our nation apart from almost all others, including Mexico.)

“It’s a complex issue, but it’s good you’re paying attention to it,” we said as we turned into our neighborhood, figuring the Teachable Moment had expired.

But she had one more question: “Was your grandfather an illegal immigrant?”

Well, we replied, he might have been: Several years ago we went on a genealogical-research bender that we understand is common to some people our age, and, while chasing down the many rabbit trails our Gran’pa had strewn in the available public record (otherwise known as untruths, or lies), we never were able to determine whether he in fact was naturalized. It appears he wasn’t.

We did finally manage to document his point of origin---in a picturesque little village in the high mountains of a land across the sea---although he told county and parish authorities, Census takers, and the Social Security Administration that he had been born in New Orleans. It turns out he had boarded a ship by himself when he was 14, five years after his schoolteacher father had died, and made his way to New Orleans to join an older sister. He bounced around and somehow wound up in East Texas---we remember hearing stories about work in a circus, a stint in semi-pro baseball, a glass eye he supposedly acquired when struck by a line drive---and spent most of his life doing ass-busting labor.

But there was no free public schooling for him, no bilingual education or English as a Second Language to ease his transition. Nor was there any lingual infrastructure in his native tongue to ensure he’d never have to learn English: no newspapers, no TV or radio, no fellow native speakers with whom to shoot the shit. There was no church of his faith within 90 or so miles of where he lived. In those days the Ku Klux Klan frequently marched through the small downtowns of East Texas. He found it prudent to adopt a more “American-sounding” surname, again without going through the legal niceties.

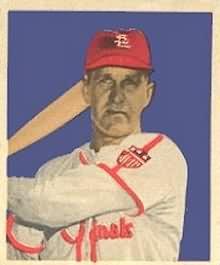

But beyond his Social Security, we doubt that he felt entitled to much of anything from his adopted country, simply because he worked hard, and it’s impossible for us to imagine him walking down the street waving the flag of the place he had voluntarily left. He became an American, with a thick Old World accent, and, from what he remember, as an old man he was content with watching the

Game of the Week with Ol’ Diz and Pee Wee on Saturday afternoons and reading the

Dallas Morning News from cover-to-cover, both of which he did while chain-smoking non-filter cigarettes with an intensity that scared our little-kid self.

Really? said our daughter, sounding relieved that the ride home, and the accompanying windy lecture, was at an end.

“So, um, you see what we’re saying about all this, right?”

“Yeah!” she replied as she fled the car.

If so, we were satisfied: We had made a 12 year old as confused and ambivalent about the issue as we are.